Ribbons and bibbons: wisdom for 2026

Illustrations by Helen Oxenbury

Verse I: Bibbons

This story starts with a gift. It ends with a murder.

On the top of the Crumpetty Tree

The Quangle Wangle sat,

But his face you could not see,

On account of his Beaver Hat.

For his Hat was a hundred and two feet wide,

With ribbons and bibbons on every side

And bells, and buttons, and loops, and lace,

So that nobody ever could see the face

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

[The Quangle Wangle’s Hat, Edward Lear]

Verse II: And Ribbons

The Buchu Bush in the indigenous garden at the front of my small Cape Town flat was like the Quangle Wangle’s hat. It took on the shape of a bowler, its pointillist haze of jungle-green foliage never needing a trim. Each spring, a bridal shower of snowy blossoms would draw Bees that’d hover as a whole, each turning on some internal gyroscope while they tended the nectar.

The Buchu was the lead act. All around it, a chorus-line of characters, performing in synch.

On a spring day in 2024, while I was off on a research trip in the Richtersveld, I got a shaky hand-filmed video showing that the Buchu Bush was gone. The whole garden was gone. While I was away, the Upstairs Neighbour had snuck down under the cover of my absence, and ripped it all out. Every tendril of Plectranthus, each cluster of Restio, the single Erica that had survived my light-touch approach to gardening.

[I have a Darwinian view of gardening — if a plant can survive my neglect, it deserves to stay in the gene pool.]

The Impepho, the African sage used in spiritual ceremonies and whose paper-dry yellow flowers are as much a part of my childhood memories as those of The Hobbit, Hogsback — the Eastern Cape eyrie that local lore says inspired Tolkien’s fantasy world — and The Quangle Wangle’s Hat.

Some of the Cape Honeysuckle had survived the reaper’s scythe, so maybe the Double-Collared Sunbirds would still have a bit of forage, and might continue to breakfast here as they had for the more than decade we’d shared this space. Possibly the flock of White Eyes would still materialise in the Frangipani canopy that, too, had been given a stay of execution.

I wondered if the Olive Thrush that had picked so fastidiously through the mulch during the quarantine days of the early plague would return. Or the Cape Robin-Chat. Maybe the Mole, who occasionally sculpted new contours with her ephemeral soily mounds, would continue to break the surface of this newly sterilised place.

I doubted it. This bridgehead that had been holding off the advancing urban sprawl was now gone. Each individual of each species, whose personhood added to the garden’s diversity and the reciprocity of its ecology, dead. The space was paved over with a mono-crop of grass, with one end choked off under tree bark chips.

We met in the summer of 2011, this rectangle of ground and me. The soil was naked, baked to a crust as hard as concrete. It took months the bring life back: pick-axing the surface, pounding the sods to grains, turning compost, pressing the first seedlings into the recovering earth and setting their roots free. The whole collection of life forms and processes — microbes, worms, mycelium, plants, rain, sunlight, shade, insects, birds — did what they do best. Some lived. Some died. Each found their place. As a collective, they thrived, finding a state of gentle reciprocity where they became something bigger than the sum of the parts.

All that was now gone.

The new single-grass garden would need regular watering, weeding, artificial fertilisers, mowing. It was unlikely to survive summer, given how the sun hammered this neighbourhood during high noon in the hottest weeks.

The Upstairs Neighbour said he’d done this modification because the supposedly unkempt fynbos garden wasn’t human-friendly, that his kids needed more room to play, that he wanted somewhere to meditate. He’d done it, because it was his right to do so.

The Quangle Wangle said

To himself on the Crumpetty Tree, —

"Jam; and jelly; and bread;

"Are the best of food for me!

"But the longer I live on this Crumpetty Tree

"The plainer than ever it seems to me

"That very few people come this way

"And that life on the whole is far from gay!"

Said the Quangle Wangle Quee.

Verse III: The gift

Kids intimidate me. I jokingly tell parents that I don’t speak the same dialect as juvenile Homo sapiens.

This time, though, I thought I could make an effort.

A young couple had moved in to one of the upstairs apartments, with two boys at the pin-ball stage of pre-kindergarten: noisy energy, exploding in unpredictable directions.

I was selling my flat and about to head off on a multi-year mobile journalism project, so I thought it might be nice to let the boys play in the front garden until the new owner moved in. They could come and go as they liked, I said to the Upstairs Neighbour. I wasn’t that precious about the plants. I even set up a little treasure hunt for the kids one day, stringing thread around the feet of the Restios and Buchu, burying bundles of different seeds here and there with hand-scrawled messages hinting at the magic that slumbered inside each husk.

What generosity, the Upstairs Neighbour effused, what kindness. Here’s some home-baked confection, said the Wife. We’ll tidy up after the boys, they promised. We’ll tamp down their joyful shrieks.

The Upstairs Neighbour said he’d be sad when they couldn’t use the garden after I’d gone.

The season began to change, though.

A Succulent got ripped from its moorings, hurled across the paving stones and left, roots-up and grasping for purchase. Pieces of plastic and building offcuts, repurposed as toys, got trodden into the mulch.

The Upstairs Neighbour got shirty when I asked that the kids not harm the plants, that they clean up after themselves.

The Upstairs Neighbour said he wasn’t going to give up his access to the garden. He said the garden wasn’t actually attached to my flat, that it was common property. He was going to keep using it, let anyone try to stop him.

Conditions became frosty.

On the morning I packed the last of my things into the little plumber’s van that would become my home for the indefinite future, one of the boys lent over the balcony and dropped a ghob of spit onto the paving next to my foot.

But there came to the Crumpetty Tree,

Mr. and Mrs. Canary;

And they said, — "Did ever you see

"Any spot so charmingly airy?

"May we build a nest on your lovely Hat?

"Mr. Quangle Wangle, grant us that!

"O please let us come and build a nest

"Of whatever material suits you best,

"Mr. Quangle Wangle Quee!”

Verse III: Vandalism and violence

The phone’s rattle was benign. The news it brought was not.

A photograph from the estate agent, taken before the final murder took place, hinted of what was to come. It showed that two large gashes had been cut into the Honeysuckle hedge that had been slowly spreading its arms along the curved edge that marked the original fence line. It was being coaxed into a soft living boundary to replace the spiked metal bars that previously separated the garden from the comings-and-goings of other life forms in the complex.

Why, I asked the Upstairs Neighbour, why cut through the hedge?

‘Because it’s my right. I’m exercising my right to access the garden.’

‘But… but,’ I thought, but didn’t have the chance to say, ‘… if you feel that strongly that it is your right, why not continue to come and go via the gate, which is right next to the holes you cut in the fence?’

No one need to spell it out: this was an act of vandalism, a deliberate expression of violence designed to intimidate, to show dominance.

The annihilation of the entire garden, which was soon to follow, was just that too.

And besides, to the Crumpetty Tree

Came the Stork, the Duck, and the Owl;

The Snail, and the Bumble-Bee,

The Frog, and the Fimble Fowl;

(The Fimble Fowl, with a corkscrew leg;)

And all of them said, — "We humbly beg,

"We may build our homes on your lovely Hat, —

"Mr. Quangle Wangle, grant us that!

"Mr. Quangle Wangle Quee!”

Verse IV: We are multitudes

Fun fact: there are so many other life forms in our bodies that only about half of us is made up of human cells. Each of us is, indeed, made up of multitudes, thanks to the bacteria in our gut micro-biome, on our skin, in our hair, you name it.

This collection of different life forms is sloshing around in a shared body that’s around 60 percent water — water whose molecules are so timeless, they’ve witnessed the detonation of the A-bomb, the extinction of the dinosaurs, and the handiwork of blue-green algae who gave us a breathable atmosphere.

That’s quite a pedigree, by any measure.

Happy gut bacteria, we now know, make for a happy, healthful ‘us’, both in body and mood.

New research shows that if we eat highly processed food-like products, our digestive system gobbles up all the nutrients quickly, up at the top of the twirly-whirly working parts, and leaves little for later down the tract. If we eat whole foods, these take longer to digest. By the time the food gets further down the digestive system, there’s a whole lot left over. Food for the others sitting at the banquet table: the gut bacteria.

Eating real foods, rather than highly-processed faux-foods, is the ultimate act of breaking bread. It’s the original ubuntu — the African notion that ‘I am, because we are’ — because we’re eating for ourselves and our gut bacteria.

What if we humans thought of ourselves and our place on the planet in these terms, that each of us is part of the Earth’s equivalent of the gut micro-biome?

Dr. Stephan Harding invites us to do this when he draws on the Gaia Theory — the notion that Earth is a complex, self-regulating organism that is a ‘collaborative reciprocal evolving life habitat’ — and considers that humans exist within this as part of the reciprocal ecology of the whole.

This thinking is part of a fast-emerging push-back against today’s dominant world view: that humans are above nature, separate from it, that nature is here for us to dominate and own and control. That humans are the peak of evolution, the centre-point against which everything else is relative and ranked as second-best. This is a recent concoction, growing out of Garden-of-Eden religious thinking, the mechanistic Cartesian view of the world that separates body from soul and human from nature, and capitalism which has since put a price tag on everything, turning subjects into commodifiable objects.

Our gut bacteria, and the fynbos garden that was my companion for over a decade and which is no more, are a reminder of what philosopher Thomas Berry said so pithily: the universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.

That’s why I’ve written the names of the species in this story with the grammatical heft of the proper noun, rather than the lower-case common noun. Let’s see the Buchu Bush as a person with a subjective experience in this world, not buchu as a mere representation of a Linnaeun species or as an object.

We need to return to humanity’s metaphysical roots, where we understood the notion of ecology before Western science arrived and ginned up a name for it, says uber-intellect Indy Johar. We must remember that we live in an entangled world, where our behaviour — for better or worse — impacts the collective. We must step out of our individualistic, atomised sense of self and remember that we are part of a collective. #carbonpollution #climatecollapse #biodiversityloss #plasticspollution

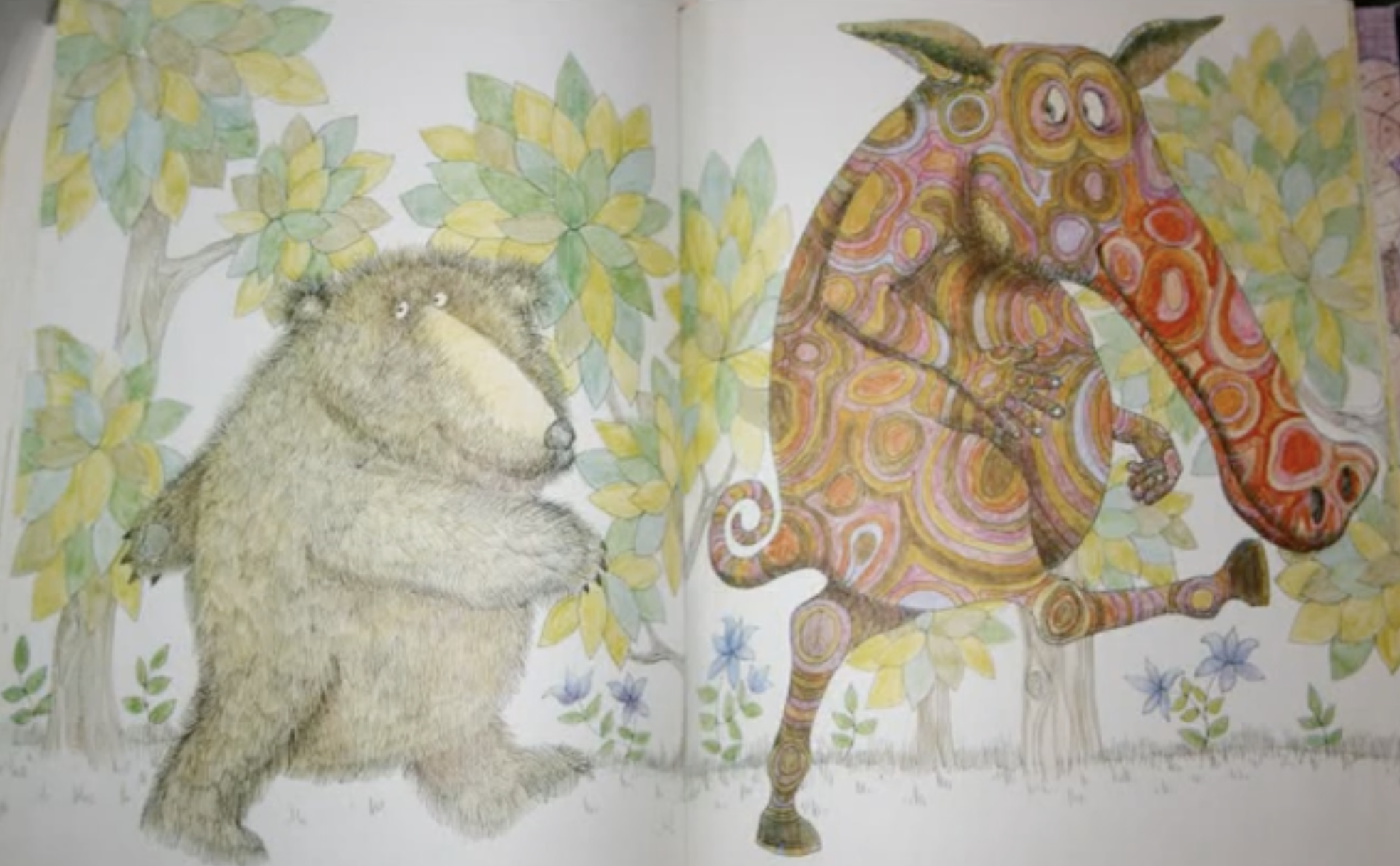

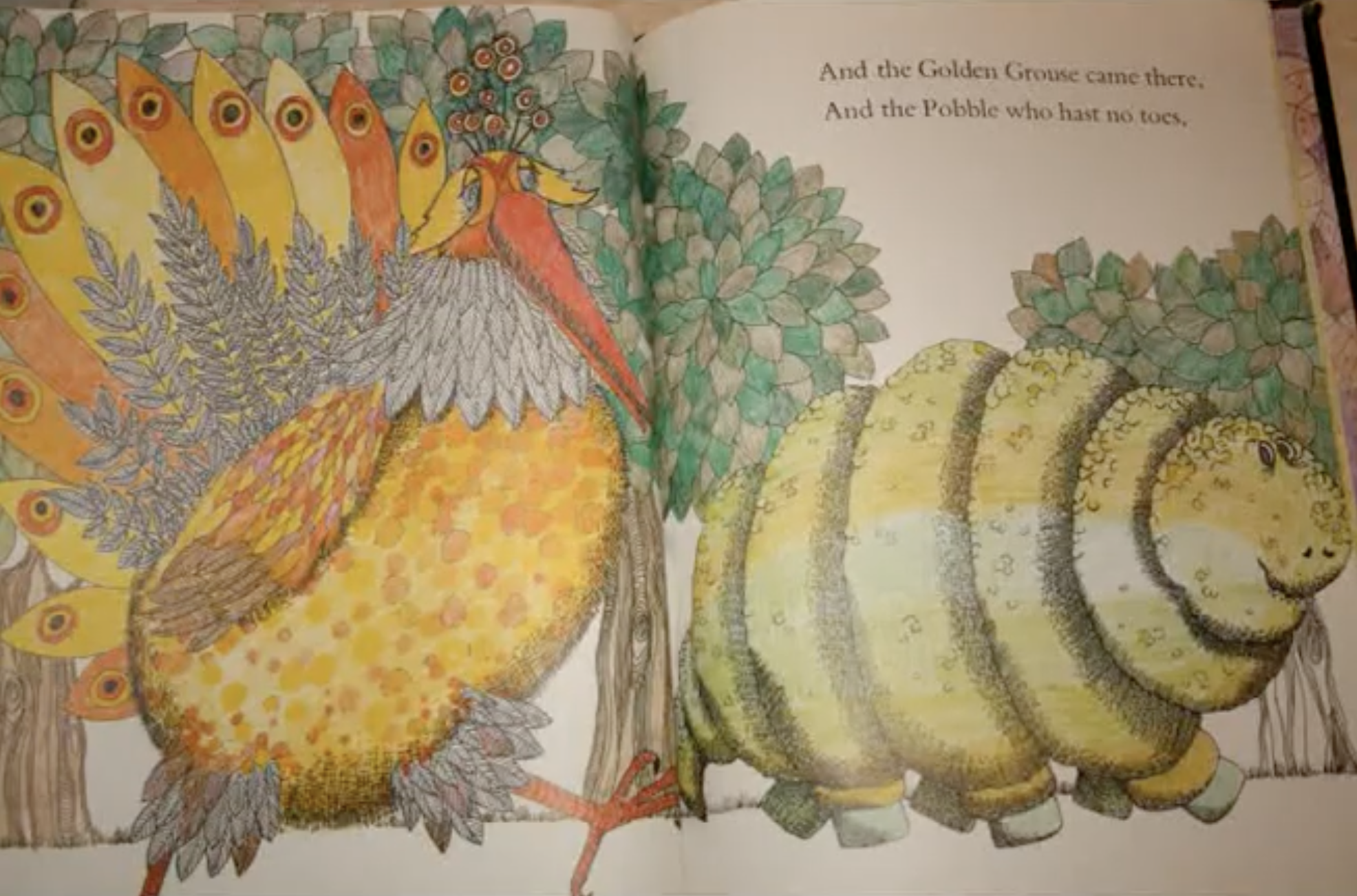

And the Golden Grouse came there,

And the Pobble who has no toes, —

And the small Olympian bear, —

And the Dong with a luminous nose.

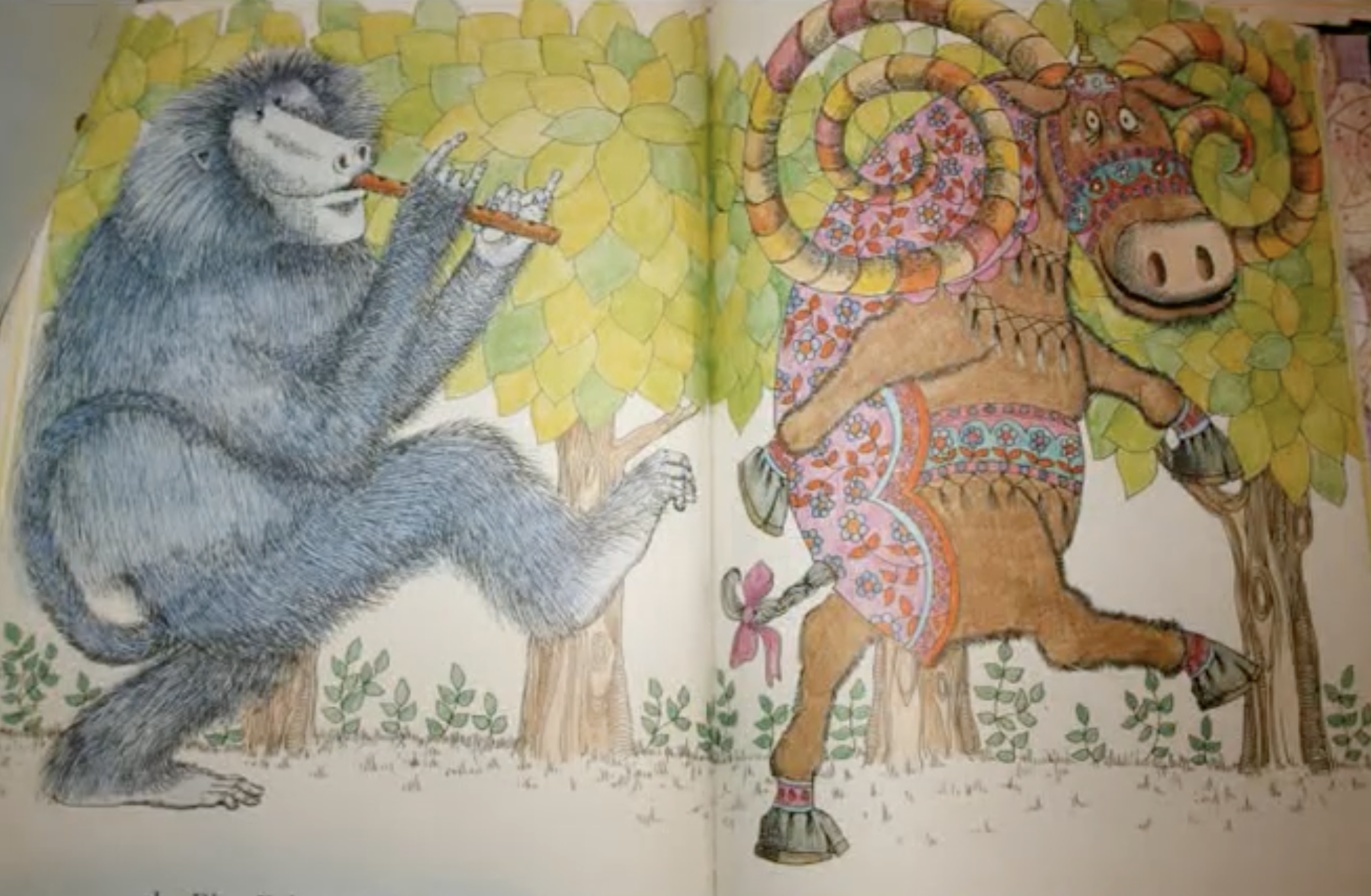

And the Blue Baboon, who played the Flute, —

And the Orient Calf from the Land of Tute, —

And the Attery Squash, and the Bisky Bat, —

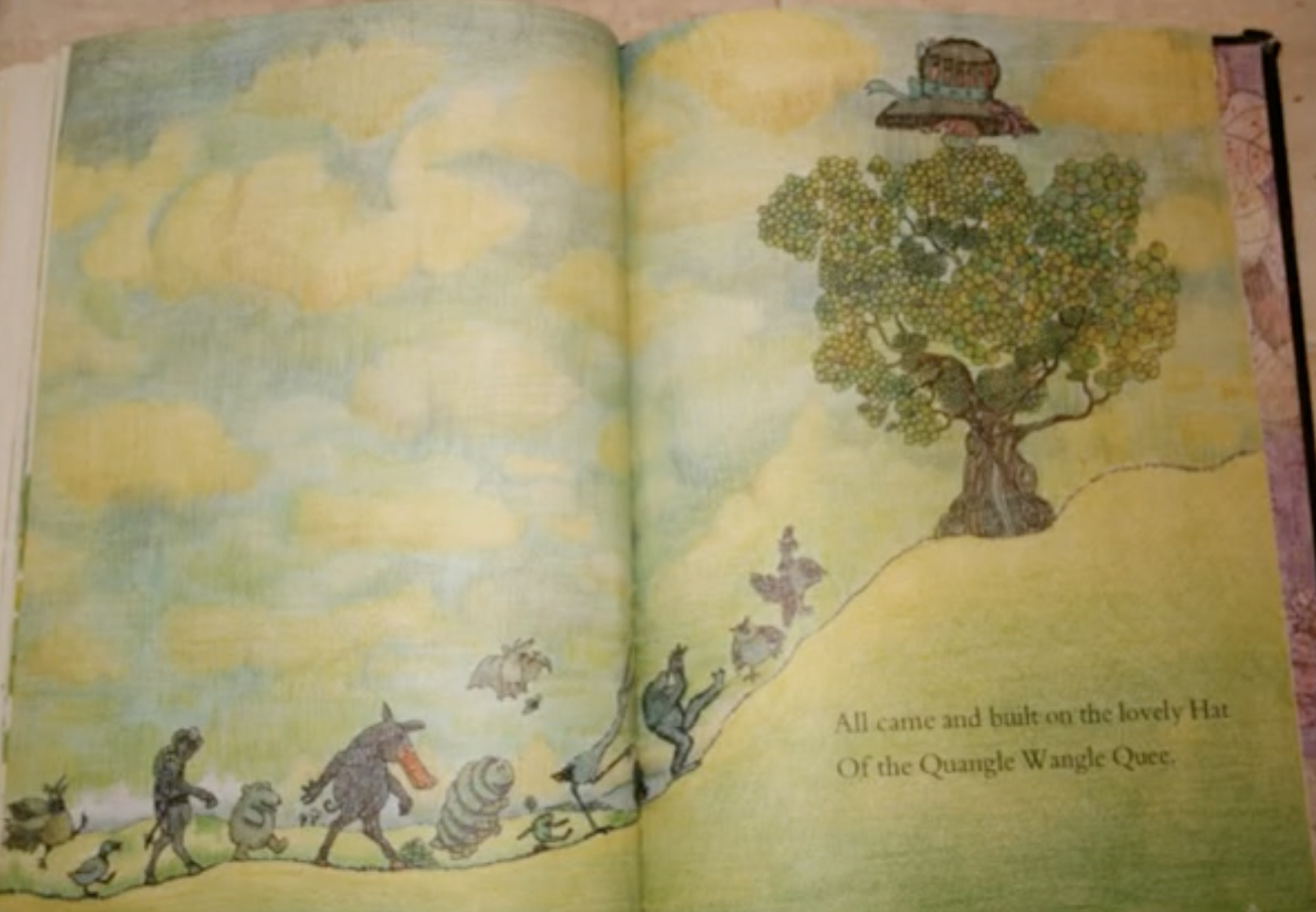

All came and built on the lovely Hat

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

Verse V: The Quangle Wangle’s kindness

This story starts with a gift. But it doesn’t have to end with a murder.

When the news came through that the Upstairs Neighbour had ripped up the fynbos garden, my rage was as unbounded as the grief was winding. This single act of wilful, selfish destruction seemed to epitomise the very reason I was on the road: a desperate last-gasp attempt to wake the world up to the destruction we’re causing to this planet and its many other life forms, out of ignorance, entitlement, selfish greed, and human exceptionalism.

Not only had the Upstairs Neighbour created a sterilised mono-crop space that worked less well than the indigenous one. He had imposed his blinkered idea of a garden aesthetic on the community around him, without even sitting down over a cup of tea to see what others might want. In his ignorance of how a natural system works, he hadn’t improved the resilience and health of the space where he wanted his kids to play, he’d throttled it. In this moment of deliberate violence, everyone in that neighbourhood was in its blast radius.

For weeks, a single thought churned in my head.

‘Imagine if I’d gathered up all your kids’ toys,’ I wanted to say to him, ‘imagine I did that, and then smashed them with a hammer, just to prove a point, just to show you that I could?’

Only, the destruction he caused wasn’t to inanimate plastic objects. It was the destruction of living beings, more-than-human life forms whose personhood was disregarded, and whose contribution to our own health ignored.

For weeks, I ruminated on this, each time feeling my ill-will towards him curdle more. As my toxicity grew, a bigger misanthropy took root.

I realised soon that if I carried on focusing my thoughts and attention on this incident, on his cruelty towards the entities in that garden, I’d only be poisoning myself.

Of course, if it were as easy as just getting over it, or just letting something go, we’d all have reached enlightenment. Each day in the months that followed the murder, I had to do a deliberate practice: see the memory, but push it to one side; notice the anger, acknowledge the pain of the murdered plants, but then re-direct the thought towards a reflection on the majesty of Gaia; choose to acknowledge the best in the human condition, rather than singularly reflecting on the worst.

As the Story Ark project launches into 2026, I am seeing each day as a chance to meditate on the bigger entity that is Gaia, and our place in it. How we can be part of the reciprocity that is the larger Earth-organism that gives us life-support systems as a gift every day.

The Buchu Bush has been slain. The individuals who made up the complex garden in which the Buchu stood so prominently are no more. But they all live on in a parable that can take us towards a relationship with each other and the more-than-human. A relationship that is not self-centred and individualistic, where exchange is not transactional, but its arranged around care and reciprocity.

We are all in this together. We’re all nesting in the Quangle Wangle’s hat, side by side, for better or worse. It is because of the Quangle Wangles’s kindness that we can gather at night by the light of the Mulberry moon and dance together to the flute of the Blue Baboon.

Within this knowledge, we have to find a way to nourish the love, and contain the hate. My quest, now as ever before, is to find the right way to tell the stories so that they win over the hearts of the Upstairs Neighbours of the world. But I’m flummoxed as to how to do that.

And the Quangle Wangle said

To himself on the Crumpetty Tree, —

"When all these creatures move

"What a wonderful noise there'll be!"

And at night by the light of the Mulberry moon

They danced to the Flute of the Blue Baboon,

On the broad green leaves of the Crumpetty Tree,

And all were as happy as happy could be,

With the Quangle Wangle Quee.