CAPTAIN’S LOG

One van, two crew, three years, all the stories.

Behind the Story Ark adventure are a whole lot of misadventures: getting bogged down in sand dunes, lost in a nature reserve, tumbling down a few mountainsides, almost-spelunking through a sandstone gorge, and a fall off a fence with medieval spikes, which needed four sutures and a tetanus shot. The Captain’s Log is where you’ll find out about life on the road with the childless-cat-lady and the cat called Mouse.

The last supper

Our restaurant seating is a remake of the last supper: 12 or so of us stretched along a narrow table, leaning over each other to catch the eye of someone further along. It doesn’t have the same sense of foreboding, although it should.

A spread fit for queens, by Howick-based locavore and food activist Nikki Brighton.

Storytelling 101: show, don’t tell. Many people at the frontline of climate collapse talk about the mental toll they take from being confronted constantly by the realities of a collapsing climate, and the seeming societal indifference. I’ve often said that it creates an existential loneliness that can’t be soothed, even in the company of people. Here’s an excerpt from Invisible Ink, which shows what it’s like inside this unique kind of isolation. #influencers #generationgap #cocaine #chemo #climatecollapse #dontlookup

Our restaurant seating is a remake of the last supper: 12 or so of us stretched along a narrow table, leaning over each other to catch the eye of someone further along. It doesn’t have the same sense of foreboding, although it should.

Benoit’s just off the plane from France. His birthday surprise is a faux-vintage faux-fur party coat from all of us, and dinner at a swanky spot in town.

The place is up to the gills with Millennials and Gen-Ys who have sashayed off a boutique billboard. We’re feeling a bit like fossils from the Cretaceous — if you know what you’re looking at, we’re an impressive bunch; if you don’t, we’re about as exciting as gravel.

It’s been a while since we’ve hung out, and there’s a lot of catching up to do. Everyone’s paddling easily in the surf, but each of us is fighting against our own rip currents.

Victor’s financial adviser has done some number crunching and reckons if he wants to retire in the style to which he has become accustomed, he’s going to have to work his knuckles raw until he’s 93.

Vic says he might need to become accustomed to something a little less like this joint.

Benoit’s sister has been dancing with the Red Devil — one of the nastiest chemos — and it’s been touch-and-go after a serious post-mastectomy curveball. Jinty has had to bury a step brother, a sister-in-law, and a nephew in the course of a year. All of them gone, way too young and way too soon. The odds are impossibly cruel, and her words are still knotted up in shock. Dehlia’s shopping aisle vertigo spells are getting more tricksy. Darren has to rustle up a multi-million-dollar cost-cut on a copper mine refurb he’s overseeing, because commodity prices have nose-dived and the mine owner can’t foot the original bill.

We’re playing nicely in the waves, but we’re trying not to get our limbs tangled as we struggle against the undercurrents.

Victor breaks in with his usual panache.

‘So,’ he says, short of a drumroll. ‘I just met an ‘influencer’.’

He'd copped a ticket to a fancy-pants lunch with a bunch of mining sector corporates and there’s someone at the table who has nothing whatsoever to do with mining. She’s there because she has a million or so followers on a social media platform. In exchange for lunch, she’ll post pictures of herself at the restaurant, hanging with the mining dudes.

It’s not clear why her followers would be interested in the goings-on of a bunch of mining industry insiders, but there you go, this is the strange new world of advertising.

‘So I ask her what she’s trying to influence. And she’s like ‘What do you mean, what am I trying to influence?’’

‘Well, you know, what’s your cause? If you’ve got this platform to influence people, what are you using it for? Are you raising awareness around, I dunno, something like teenage pregnancy or…?’

‘Oh! No, no,’ she hoots, looking at him as though he has, in fact, crawled out of the fossil record. ‘It’s so I can travel around for free. I tell hotels and restaurants that I’ve got all these followers, and they let me stay for free, and I post pictures of myself in their places.’

Now we definitely feel like geological relics, so we steer back to things that are more familiar to our epoch.

Benoit tells us what it’s been like in Europe these past weeks. The place has been melting like a Dali painting, with temperatures smashing records across the continent. It looks as though Bordeaux may only have a few more harvests left before it becomes too hot for palatable wine. The Rhine has all but shrivelled, so much so that only the smaller barges can still ferry goods up and down this historic transport route for the summer. His brother-in-law’s thinking of moving the family somewhere safer, somewhere in Europe that’s less climate vulnerable. But where’s safe?

The elephant in the conversation: the fledglings amongst our group of friends, the teenagers who will be leaving the nest just as the world is catching fire. How on Earth do we protect them from this, apologise to them for it, live with ourselves as we hand them the baton of adulthood and a fiery hell-Earth.

My bladder has reached carrying capacity, though, so it’s off to the water closet.

One cubicle is occupied. The doorway to the other is blocked by two sleek 20-somethings who are comparing fashion bona fides and trading notes about who to keep an Insta-eye on for the best makeup tips.

I can’t tell if they’re heading into the loo, or out, but either way they’re stuck in transit.

I start a queue of one.

Chatter, chatter, chatter.

I wait.

Chatter, chatter, chatter.

They’re not budging.

Chatter, chatter, chatter.

I’m about to suggest that if they’re there for a bump — judging by the cadence of their speech, they might be — they could cut their lines out here on the basin counter, so that I can get to the porcelain. Would speed things up a bit?

I’m intrigued, though. Have they not noticed that someone else needs the loo, or are they simply unmoved? I’m an anthropologist perched on the banks of the generation gap, jotting down notes. Prehistoric fossil here, Millennials there.

Are they the influencers or the influenced?

Is this what Roger Waters sings about, that we’ve amused ourselves to death?

I want to scream into their bubble: ‘Look up! Look up! The meteors! The meteors! You have to look UP!’

But if I do, I’d have to fess up to my part in summoning in the rain of fire.

They might also think I’m batshit crazy — and they’d only be partly wrong — so I stay shtum.

Bathroom etiquette and the laws of physics are against me, though. There are only so many extra mills a bladder can take before it starts to bust a seam.

I cross my ankles and hop on one foot.

And just like that, it’s over. Without a glance, they pivot on their glossy heels and are out the door.

It’s three years since 2019 shocked my hair curly, and two since the World Health Organization placed us under temporary house arrest. The virus will never be done, the UN is finally telling us, but the pandemic is over. The prison doors are finally sliding open.

We still feel naked without our masks, though, and everything is a bit squiffy. Jinty calls it the Sleeping Beauty Syndrome. It’s as if we’ve woken from a long sleep and everything’s slightly strange. How do we reconcile with our new selves? How do we reemerge?

Back at the table, the wine bottles are emptying fast.

I’ve been off the booze for months — my menopause survival strategy, I tell everyone, to stop the ballooning weight and all that — but the truth is that my dicky nerves can’t cope with alcohol, and it gives me the chronic blues. It’s too high a price to pay for the momentary satisfaction of a mouthful of good Cabernet, no matter how well-aged in whatever kind of oak.

It means I’m not reading from the same sheet music as everyone else. My repertoire of talking points is limited to extreme this and catastrophic that. Not a great pairing for a breezy Friday night. I can’t keep inflicting my misery on these good people.

My throat clogs with unformed words.

The past three years have broken my brain. I’m throwing everything I have at the task of gluing it back together, but the last thing on the doctor’s prescription is the one thing you can’t get from a dispensing pharmacy. Get out of your head and out of your hermitage, Mark the New Therapist says. You have to reconnect with others.

The guy ropes that moor us together in conversation are our reciprocal exchange, but the grappling hooks on the ends of my efforts are barbed with anxiety.

If I can’t add to the chatter, I can at least look like I’m part of it. Body language speaks way louder than words, right? Tonight’s mindful intervention: edit the body language to better integrate into the group. That’s the plan.

I winch the sides of my mouth into a smile — fake it ’til you make it, yeah?

My head works like a deranged Bobblehead as I follow everyone’s banter, although the laughter may be a bit loud.

Darren, from the far end of the table: ’Leo! Why so glum!?’

Me: ‘…………’

I am Judas, exposed.

The smokers on the pavement outside open their huddle, and I shelter in its anonymity as the drizzle simmers electrically against the streetlights.

When this whole damn story finally went Chernobyl earlier in 2022, Mark the New Therapist was one of the first responders. Most of what we do in the months that follow is figure out how much of what’s going on in my head is real and how much is make-believe. The whole Plato’s cave conundrum: how much of what you’re seeing in the world is the shadow on the wall, and how much is the reality of the figure casting the shadow?

‘Have you seen the movie Don’t Look Up?’ I ask him during one of our first meetings.

He nods.

‘You know that scene at the end of the movie, where those people who tried to warn everyone about the asteroid are sitting around the table?’

Nods again.

It’s the last supper. They’re gathered for a final communion. It’s not about the food on their plates. They’re hardly touching the wine. They’re making small talk. Mostly, they’re not looking at the time.

They’re there because they want to be together in their last moments.

One or two of them take hands. The cutlery begins to tremble. The camera pans out. The asteroid is incoming, and it’s a fucking monster.

‘I feel as though I’m at that table,’ I tell Mark. ‘Only, I’m all alone.’

Ribbons and bibbons: wisdom for 2026

This story starts with a gift. It ends with a murder.

Illustrations by Helen Oxenbury

Verse I: Bibbons

This story starts with a gift. It ends with a murder.

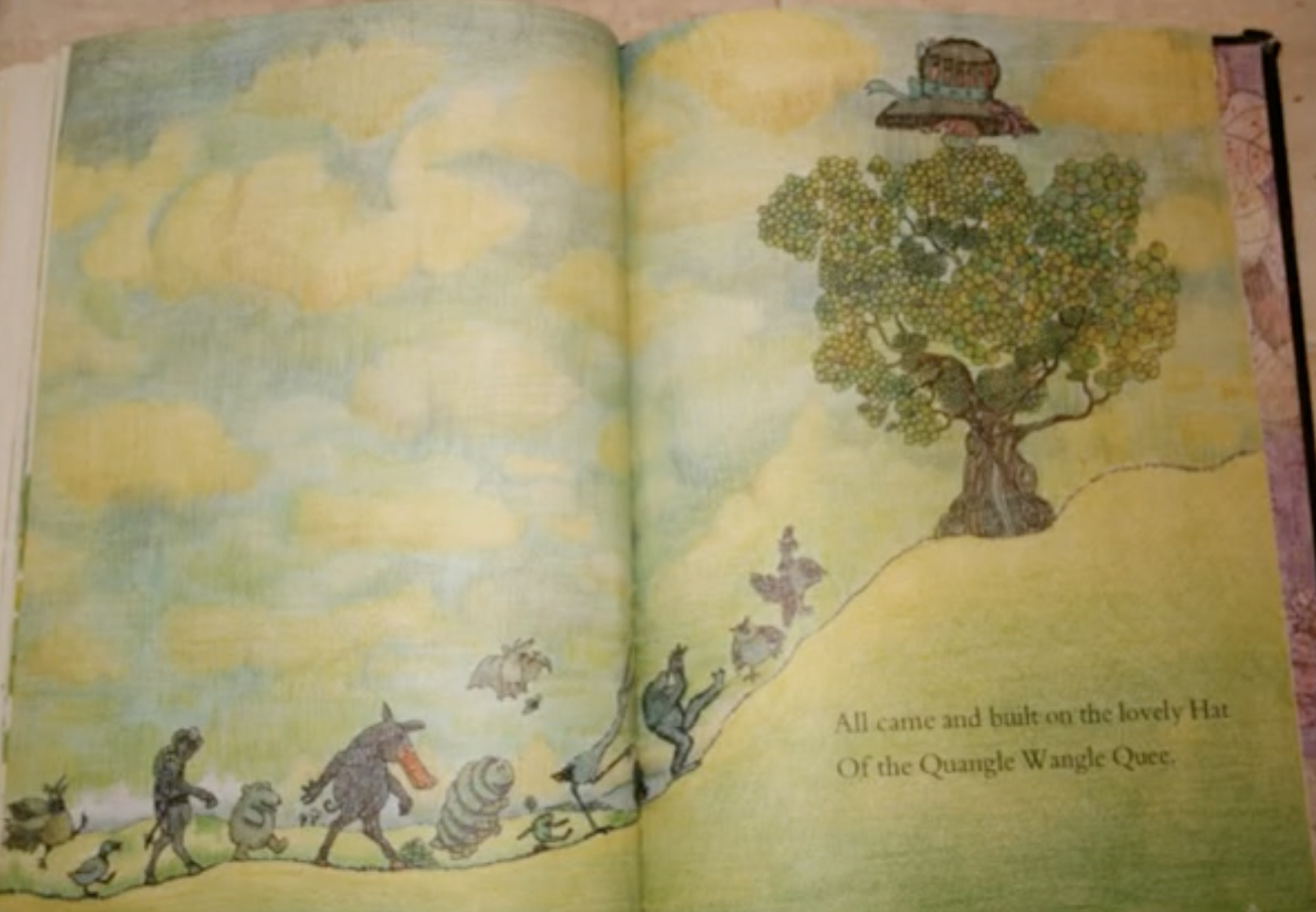

On the top of the Crumpetty Tree

The Quangle Wangle sat,

But his face you could not see,

On account of his Beaver Hat.

For his Hat was a hundred and two feet wide,

With ribbons and bibbons on every side

And bells, and buttons, and loops, and lace,

So that nobody ever could see the face

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

[The Quangle Wangle’s Hat, Edward Lear]

Verse II: And Ribbons

The Buchu Bush in the indigenous garden at the front of my small Cape Town flat was like the Quangle Wangle’s hat. It took on the shape of a bowler, its pointillist haze of jungle-green foliage never needing a trim. Each spring, a bridal shower of snowy blossoms would draw Bees that’d hover as a whole, each turning on some internal gyroscope while they tended the nectar.

The Buchu was the lead act. All around it, a chorus-line of characters, performing in synch.

On a spring day in 2024, while I was off on a research trip in the Richtersveld, I got a shaky hand-filmed video showing that the Buchu Bush was gone. The whole garden was gone. While I was away, the Upstairs Neighbour had snuck down under the cover of my absence, and ripped it all out. Every tendril of Plectranthus, each cluster of Restio, the single Erica that had survived my light-touch approach to gardening.

[I have a Darwinian view of gardening — if a plant can survive my neglect, it deserves to stay in the gene pool.]

The Impepho, the African sage used in spiritual ceremonies and whose paper-dry yellow flowers are as much a part of my childhood memories as those of The Hobbit, Hogsback — the Eastern Cape eyrie that local lore says inspired Tolkien’s fantasy world — and The Quangle Wangle’s Hat.

Some of the Cape Honeysuckle had survived the reaper’s scythe, so maybe the Double-Collared Sunbirds would still have a bit of forage, and might continue to breakfast here as they had for the more than decade we’d shared this space. Possibly the flock of White Eyes would still materialise in the Frangipani canopy that, too, had been given a stay of execution.

I wondered if the Olive Thrush that had picked so fastidiously through the mulch during the quarantine days of the early plague would return. Or the Cape Robin-Chat. Maybe the Mole, who occasionally sculpted new contours with her ephemeral soily mounds, would continue to break the surface of this newly sterilised place.

I doubted it. This bridgehead that had been holding off the advancing urban sprawl was now gone. Each individual of each species, whose personhood added to the garden’s diversity and the reciprocity of its ecology, dead. The space was paved over with a mono-crop of grass, with one end choked off under tree bark chips.

We met in the summer of 2011, this rectangle of ground and me. The soil was naked, baked to a crust as hard as concrete. It took months the bring life back: pick-axing the surface, pounding the sods to grains, turning compost, pressing the first seedlings into the recovering earth and setting their roots free. The whole collection of life forms and processes — microbes, worms, mycelium, plants, rain, sunlight, shade, insects, birds — did what they do best. Some lived. Some died. Each found their place. As a collective, they thrived, finding a state of gentle reciprocity where they became something bigger than the sum of the parts.

All that was now gone.

The new single-grass garden would need regular watering, weeding, artificial fertilisers, mowing. It was unlikely to survive summer, given how the sun hammered this neighbourhood during high noon in the hottest weeks.

The Upstairs Neighbour said he’d done this modification because the supposedly unkempt fynbos garden wasn’t human-friendly, that his kids needed more room to play, that he wanted somewhere to meditate. He’d done it, because it was his right to do so.

The Quangle Wangle said

To himself on the Crumpetty Tree, —

"Jam; and jelly; and bread;

"Are the best of food for me!

"But the longer I live on this Crumpetty Tree

"The plainer than ever it seems to me

"That very few people come this way

"And that life on the whole is far from gay!"

Said the Quangle Wangle Quee.

Verse III: The gift

Kids intimidate me. I jokingly tell parents that I don’t speak the same dialect as juvenile Homo sapiens.

This time, though, I thought I could make an effort.

A young couple had moved in to one of the upstairs apartments, with two boys at the pin-ball stage of pre-kindergarten: noisy energy, exploding in unpredictable directions.

I was selling my flat and about to head off on a multi-year mobile journalism project, so I thought it might be nice to let the boys play in the front garden until the new owner moved in. They could come and go as they liked, I said to the Upstairs Neighbour. I wasn’t that precious about the plants. I even set up a little treasure hunt for the kids one day, stringing thread around the feet of the Restios and Buchu, burying bundles of different seeds here and there with hand-scrawled messages hinting at the magic that slumbered inside each husk.

What generosity, the Upstairs Neighbour effused, what kindness. Here’s some home-baked confection, said the Wife. We’ll tidy up after the boys, they promised. We’ll tamp down their joyful shrieks.

The Upstairs Neighbour said he’d be sad when they couldn’t use the garden after I’d gone.

The season began to change, though.

A Succulent got ripped from its moorings, hurled across the paving stones and left, roots-up and grasping for purchase. Pieces of plastic and building offcuts, repurposed as toys, got trodden into the mulch.

The Upstairs Neighbour got shirty when I asked that the kids not harm the plants, that they clean up after themselves.

The Upstairs Neighbour said he wasn’t going to give up his access to the garden. He said the garden wasn’t actually attached to my flat, that it was common property. He was going to keep using it, let anyone try to stop him.

Conditions became frosty.

On the morning I packed the last of my things into the little plumber’s van that would become my home for the indefinite future, one of the boys lent over the balcony and dropped a ghob of spit onto the paving next to my foot.

But there came to the Crumpetty Tree,

Mr. and Mrs. Canary;

And they said, — "Did ever you see

"Any spot so charmingly airy?

"May we build a nest on your lovely Hat?

"Mr. Quangle Wangle, grant us that!

"O please let us come and build a nest

"Of whatever material suits you best,

"Mr. Quangle Wangle Quee!”

Verse III: Vandalism and violence

The phone’s rattle was benign. The news it brought was not.

A photograph from the estate agent, taken before the final murder took place, hinted of what was to come. It showed that two large gashes had been cut into the Honeysuckle hedge that had been slowly spreading its arms along the curved edge that marked the original fence line. It was being coaxed into a soft living boundary to replace the spiked metal bars that previously separated the garden from the comings-and-goings of other life forms in the complex.

Why, I asked the Upstairs Neighbour, why cut through the hedge?

‘Because it’s my right. I’m exercising my right to access the garden.’

‘But… but,’ I thought, but didn’t have the chance to say, ‘… if you feel that strongly that it is your right, why not continue to come and go via the gate, which is right next to the holes you cut in the fence?’

No one need to spell it out: this was an act of vandalism, a deliberate expression of violence designed to intimidate, to show dominance.

The annihilation of the entire garden, which was soon to follow, was just that too.

And besides, to the Crumpetty Tree

Came the Stork, the Duck, and the Owl;

The Snail, and the Bumble-Bee,

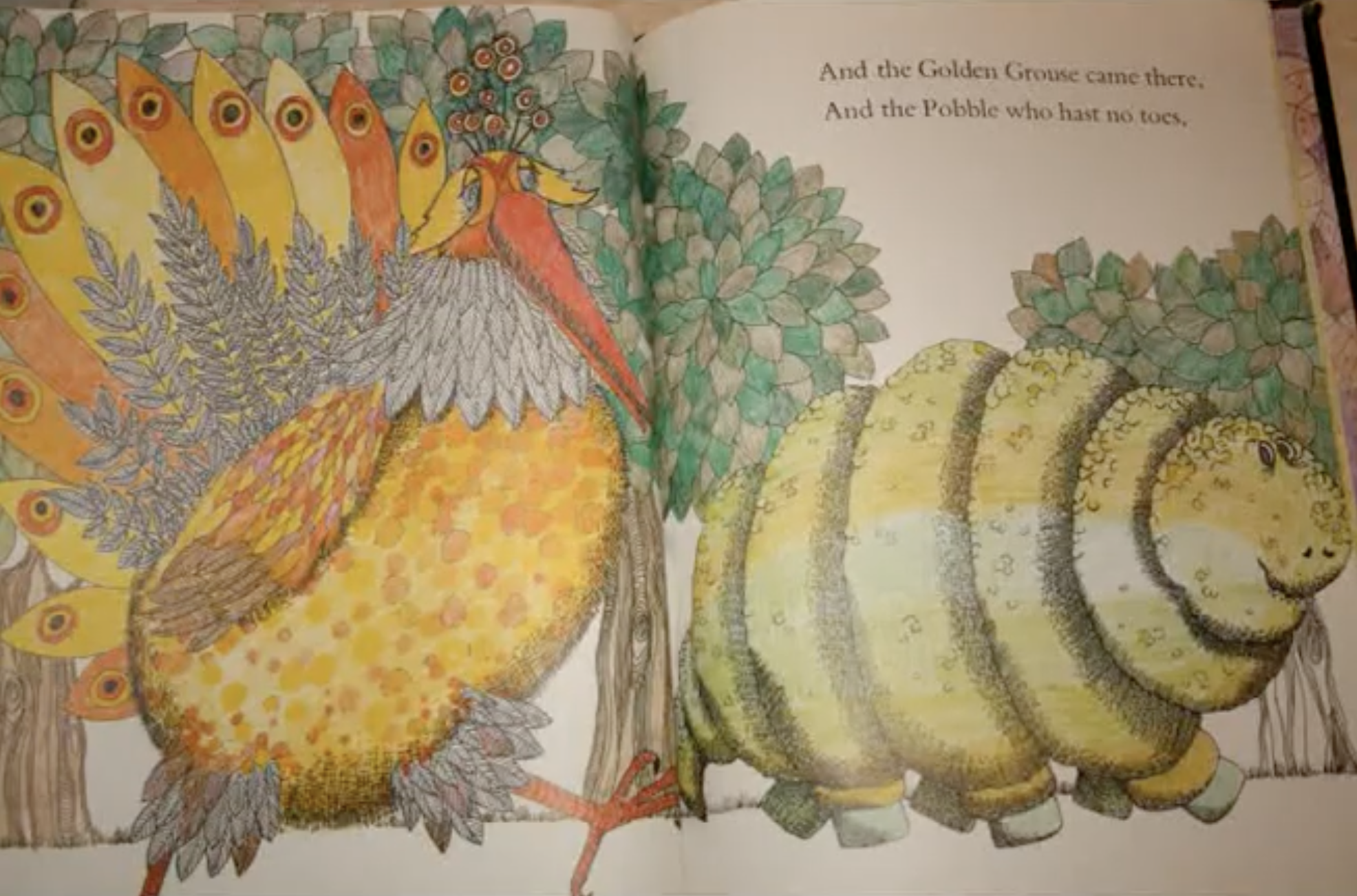

The Frog, and the Fimble Fowl;

(The Fimble Fowl, with a corkscrew leg;)

And all of them said, — "We humbly beg,

"We may build our homes on your lovely Hat, —

"Mr. Quangle Wangle, grant us that!

"Mr. Quangle Wangle Quee!”

Verse IV: We are multitudes

Fun fact: there are so many other life forms in our bodies that only about half of us is made up of human cells. Each of us is, indeed, made up of multitudes, thanks to the bacteria in our gut micro-biome, on our skin, in our hair, you name it.

This collection of different life forms is sloshing around in a shared body that’s around 60 percent water — water whose molecules are so timeless, they’ve witnessed the detonation of the A-bomb, the extinction of the dinosaurs, and the handiwork of blue-green algae who gave us a breathable atmosphere.

That’s quite a pedigree, by any measure.

Happy gut bacteria, we now know, make for a happy, healthful ‘us’, both in body and mood.

New research shows that if we eat highly processed food-like products, our digestive system gobbles up all the nutrients quickly, up at the top of the twirly-whirly working parts, and leaves little for later down the tract. If we eat whole foods, these take longer to digest. By the time the food gets further down the digestive system, there’s a whole lot left over. Food for the others sitting at the banquet table: the gut bacteria.

Eating real foods, rather than highly-processed faux-foods, is the ultimate act of breaking bread. It’s the original ubuntu — the African notion that ‘I am, because we are’ — because we’re eating for ourselves and our gut bacteria.

What if we humans thought of ourselves and our place on the planet in these terms, that each of us is part of the Earth’s equivalent of the gut micro-biome?

Dr. Stephan Harding invites us to do this when he draws on the Gaia Theory — the notion that Earth is a complex, self-regulating organism that is a ‘collaborative reciprocal evolving life habitat’ — and considers that humans exist within this as part of the reciprocal ecology of the whole.

This thinking is part of a fast-emerging push-back against today’s dominant world view: that humans are above nature, separate from it, that nature is here for us to dominate and own and control. That humans are the peak of evolution, the centre-point against which everything else is relative and ranked as second-best. This is a recent concoction, growing out of Garden-of-Eden religious thinking, the mechanistic Cartesian view of the world that separates body from soul and human from nature, and capitalism which has since put a price tag on everything, turning subjects into commodifiable objects.

Our gut bacteria, and the fynbos garden that was my companion for over a decade and which is no more, are a reminder of what philosopher Thomas Berry said so pithily: the universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.

That’s why I’ve written the names of the species in this story with the grammatical heft of the proper noun, rather than the lower-case common noun. Let’s see the Buchu Bush as a person with a subjective experience in this world, not buchu as a mere representation of a Linnaeun species or as an object.

We need to return to humanity’s metaphysical roots, where we understood the notion of ecology before Western science arrived and ginned up a name for it, says uber-intellect Indy Johar. We must remember that we live in an entangled world, where our behaviour — for better or worse — impacts the collective. We must step out of our individualistic, atomised sense of self and remember that we are part of a collective. #carbonpollution #climatecollapse #biodiversityloss #plasticspollution

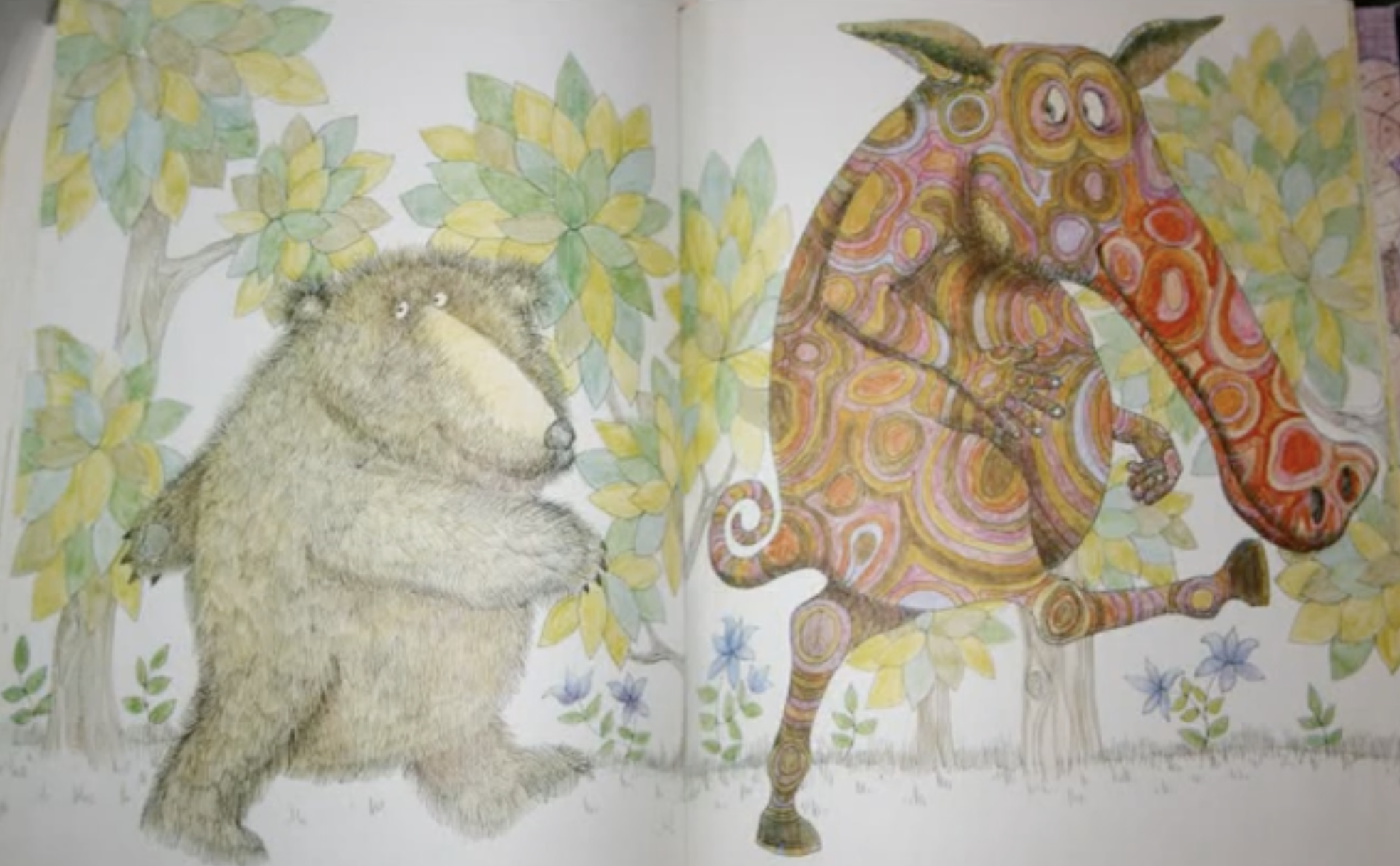

And the Golden Grouse came there,

And the Pobble who has no toes, —

And the small Olympian bear, —

And the Dong with a luminous nose.

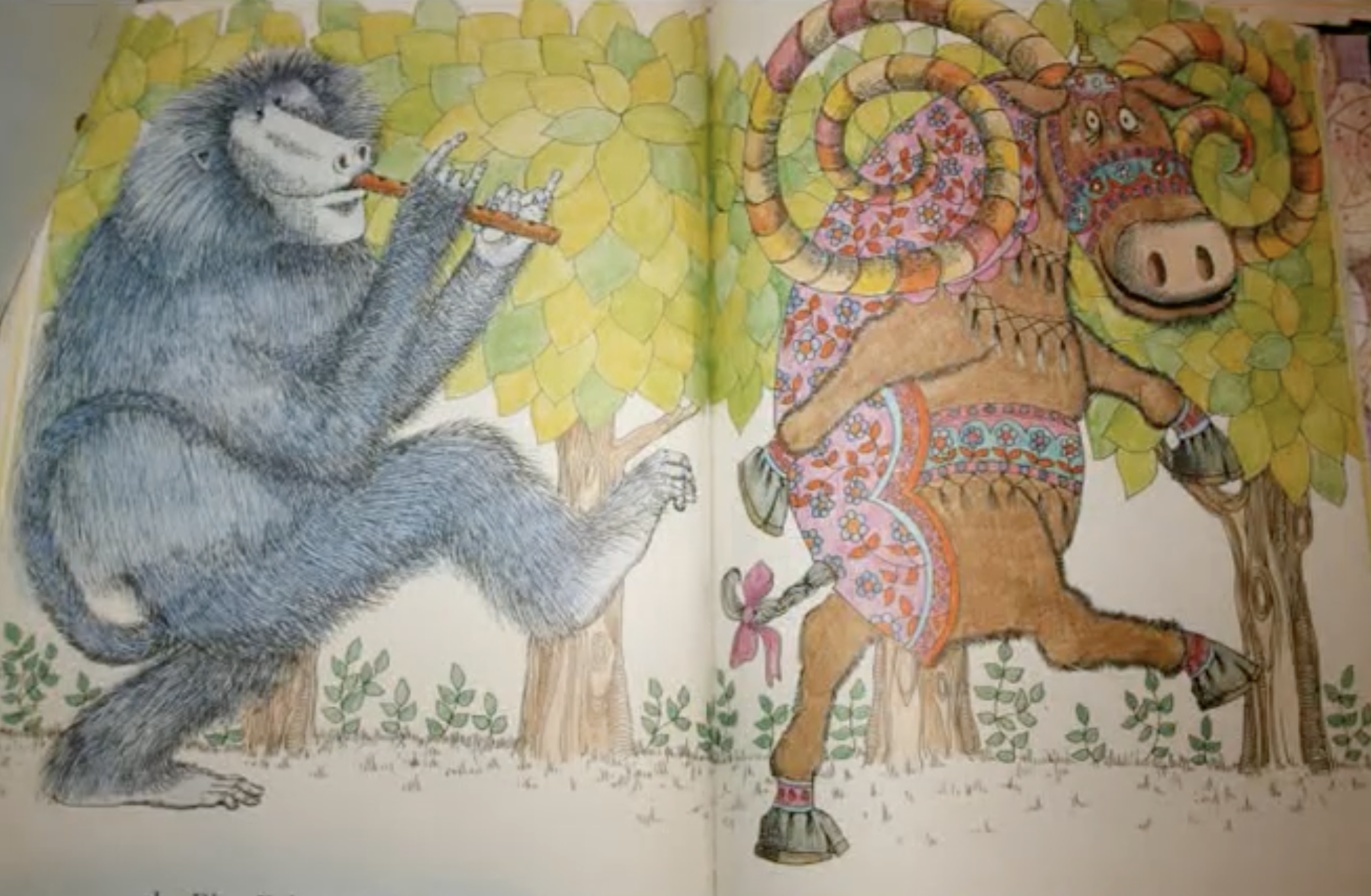

And the Blue Baboon, who played the Flute, —

And the Orient Calf from the Land of Tute, —

And the Attery Squash, and the Bisky Bat, —

All came and built on the lovely Hat

Of the Quangle Wangle Quee.

Verse V: The Quangle Wangle’s kindness

This story starts with a gift. But it doesn’t have to end with a murder.

When the news came through that the Upstairs Neighbour had ripped up the fynbos garden, my rage was as unbounded as the grief was winding. This single act of wilful, selfish destruction seemed to epitomise the very reason I was on the road: a desperate last-gasp attempt to wake the world up to the destruction we’re causing to this planet and its many other life forms, out of ignorance, entitlement, selfish greed, and human exceptionalism.

Not only had the Upstairs Neighbour created a sterilised mono-crop space that worked less well than the indigenous one. He had imposed his blinkered idea of a garden aesthetic on the community around him, without even sitting down over a cup of tea to see what others might want. In his ignorance of how a natural system works, he hadn’t improved the resilience and health of the space where he wanted his kids to play, he’d throttled it. In this moment of deliberate violence, everyone in that neighbourhood was in its blast radius.

For weeks, a single thought churned in my head.

‘Imagine if I’d gathered up all your kids’ toys,’ I wanted to say to him, ‘imagine I did that, and then smashed them with a hammer, just to prove a point, just to show you that I could?’

Only, the destruction he caused wasn’t to inanimate plastic objects. It was the destruction of living beings, more-than-human life forms whose personhood was disregarded, and whose contribution to our own health ignored.

For weeks, I ruminated on this, each time feeling my ill-will towards him curdle more. As my toxicity grew, a bigger misanthropy took root.

I realised soon that if I carried on focusing my thoughts and attention on this incident, on his cruelty towards the entities in that garden, I’d only be poisoning myself.

Of course, if it were as easy as just getting over it, or just letting something go, we’d all have reached enlightenment. Each day in the months that followed the murder, I had to do a deliberate practice: see the memory, but push it to one side; notice the anger, acknowledge the pain of the murdered plants, but then re-direct the thought towards a reflection on the majesty of Gaia; choose to acknowledge the best in the human condition, rather than singularly reflecting on the worst.

As the Story Ark project launches into 2026, I am seeing each day as a chance to meditate on the bigger entity that is Gaia, and our place in it. How we can be part of the reciprocity that is the larger Earth-organism that gives us life-support systems as a gift every day.

The Buchu Bush has been slain. The individuals who made up the complex garden in which the Buchu stood so prominently are no more. But they all live on in a parable that can take us towards a relationship with each other and the more-than-human. A relationship that is not self-centred and individualistic, where exchange is not transactional, but its arranged around care and reciprocity.

We are all in this together. We’re all nesting in the Quangle Wangle’s hat, side by side, for better or worse. It is because of the Quangle Wangles’s kindness that we can gather at night by the light of the Mulberry moon and dance together to the flute of the Blue Baboon.

Within this knowledge, we have to find a way to nourish the love, and contain the hate. My quest, now as ever before, is to find the right way to tell the stories so that they win over the hearts of the Upstairs Neighbours of the world. But I’m flummoxed as to how to do that.

And the Quangle Wangle said

To himself on the Crumpetty Tree, —

"When all these creatures move

"What a wonderful noise there'll be!"

And at night by the light of the Mulberry moon

They danced to the Flute of the Blue Baboon,

On the broad green leaves of the Crumpetty Tree,

And all were as happy as happy could be,

With the Quangle Wangle Quee.

Custard, crown jewels, and the Cullinans

What does this weekend’s anti-inequality protest in the Tower of London have to do with the environmental lawyer whose keynote address opened the World Conference of Science Journalists far away in South Africa?

Everything. The clue is right there in the name.

Screengrab from a Youtube video on The Guardian website.

What does this weekend’s anti-inequality protest in the Tower of London have to do with the environmental lawyer whose keynote address opened the World Conference of Science Journalists far away in South Africa?

Everything. The clue is right there in the name.

The protest couldn’t have been more British if it’d tried. A non-violent act of civil disobedience in which young British activists pelted a display case housing the Imperial State Crown — arguably the alpha-male of the crown jewel collection — with apple crumble, and topped it off with custard.

Their rallying cry: to draw attention to the gross inequality in their country. The same inequality we see the world over.

The UK’s crown jewels epitomise the extractive colonial project that allowed a few to amass enormous wealth at the cost of the majority. The capitalist project picked up where colonialism ended, and both have set the planet on a path of ecological ruin and likely mass extinction.

Front and centre of the Imperial State Crown is a singularly magnificent gem: the eye-wateringly opulent Cullinan diamond. At least, a piece of the diamond that still holds the record for being the largest gem-quality diamond ever found, and which was cut down into nine pieces.

The story here isn’t that the Star of Africa gem was found at a mine just an hour’s drive from the Pretoria venue where the World Conference of Science Journalists (WCSJ) took place for the first time on Africa soil.

The story is that the environmental lawyer whose keynote address opened the event is directly linked to the Cullinan family on whose farm this gem was found.

While Cullinan-the-diamond — along with the Imperial State Crown — represents the very extractivism that created so much inequality globally, Cullinan-the-lawyer was at the conference to present an emerging idea that is regarded by many as the very antidote to that predatory exploitation of the planet, its inhabitants, both human and more-than-human that got us into this mess in the first place. #AmitavGhosh #NutmegsCurse #JeremyLent #PatterningInstinct

Cormac Cullinan unveiled at the conference an idea whose time many will say has come: the notion that giving legal rights and status to Nature can help arrest our plummet towards mass systems collapse and likely extinction.

Cullinan-the-lawyer has been at the forefront of the global rights of nature movement which, in its own words, calls for the ‘recognition that our ecosystems – including trees, oceans, animals, mountains – have rights just as human beings have rights. Rights of Nature is about balancing what is good for human beings against what is good for other species, what is good for the planet as a world. It is the holistic recognition that all life, all ecosystems on our planet are deeply intertwined.’

#MothRights #RobertMacfarlane #IsARiverAlive?

The Cullinan family connection is a bit complicated, but stay with me because it adds even more depth to this unlikely unfolding of events: Cormac Cullinan isn’t the direct biological line of Thomas Cullinan who owned the farm where the bit-of-bling was found. He’s married to Mary Ann ‘Max’ Cullinan, who is a direct descendent. Both Mary Ann and Cormac happened to have the same last names when they met, which made the legal paperwork of their union simple but complicated things when explaining that they weren’t related before their marriage.

In many ways, South Africa is a microcosm of the state of the world today: a country where a few powerful elite were able to capture the commons — the resources, minerals, human ‘capital’ (I say that reservedly, because human beings aren’t units of capital) — and amass enormous wealth and political power at the cost of the majority.

Mary Ann and Cormac Cullinan are a tour de force in this context, both having committed much of their lives to working to undermine the illegitimate white minority apartheid state in South Africa, and now becoming a voice for the humans and more-than-humans who are suffering for being on the wrong side of the power divide in today’s highly unequal global system.

We could quibble about how valid this link is — Cullinan-the-lawyer is only married into Cullinan-the-family, there’s no genetic link. But genetics are only one way that we can trace family trees. More important, here, is the memetic link. Here I’m using the original idea of the meme, coined first by geneticist Richard Dawkins, who proposed the notion that ideas can spread the way genes do.

Ideas matter. Ideas can be dangerous.*

You couldn’t have scripted the past week’s events better: to have Cullinan-the-lawyer open the WCSJ with the idea of the Rights of Nature movement, at a venue just an hour’s drive from where the Cullinan-the-diamond was found, while at the same time having activists apple-crumble a piece of bling that the UK’s monarch wore at the coronation earlier this year and whose centre-piece is a chunk of that very Cullinan diamond.

As we say in South Africa: nooit, bru!

*I regard myself as a memetic parent, not a genetic one. Which is why JD Vance should worry his pretty little head about us childless cat ladies, because our every existence upends the patriarchy that he and his MAGA followers cling to so desperately. Imagine what our ideas can do?

The Devil’s breath

There’ve only been three times in the past year where I’ve thought I might have to throw in the towel on the Story Ark voyage.

Each time, because of fear.

Fear, brought on by heat.

Cat under a hot tin roof: Mouse is usually 3.5kg of split-the-atom charisma, but even she was floored by the heat.*

There’ve only been three times in the past year where I’ve thought I might have to throw in the towel on the Story Ark voyage.

Each time, because of fear.

Fear, brought on by heat.

Heat One: departure day

As if sailing away from everything safe and familiar wasn’t hard enough, departure day on 6 October 2024 was like heading directly into the Devil’s breath: half a day’s drive from Cape Town, its safe harbour disappearing beyond the distant curvature of the horizon. The van’s thermometer nearly broke its housing as we approached Clanwilliam, hitting 39°C.

Heat Two: foul vapours

Setting up camp two months later on the banks of the Gourtiz River in 38°C, followed by a week of wind storm that felt like it came straight from the belly of the beast: all acid reflux, bile, and foul vapours. I fled, with shattered tent poles and a mood approaching Chernobyl-level meltdown, and limped across the breadth of the country to find safe harbour in the Eastern Cape grasslands.

Heat Three: not-so-hot-day

Last Sunday, it happened again.

It wasn’t even that hot: 26°C, if the flaming red digits on the cab’s dashboard were anything to go by. But when I swung open the door of the — well, they called it a chalet but really it was just a Wendy house. In South Africa, a Wendy house isn’t the play house from the Peter Pan story. It’s what we call the permanent homes that aren’t quite informal shacks, but nothing as palatial as a bricks-n-mortar home. We also call them hokkies, as in a chicken coop.

I’d booked this chalet for a week-long research trip in south Durban, near where I hoped to spend time visiting families in the Dakota Beach informal settlement. The plan was to hear about life in Dakota and how they experience extreme events when they’re living in homes made from found materials like wooden boards or tin.

The people who’d agreed to meet have been part of a research effort that’s mapping how hot the inside of their homes are compared with outside conditions. Over the past summer, they’d had temperature-reading devices called i-buttons fitted a few centimetres beneath their roofs in order to record daily indoor temperatures. These homes are made of board, tin sheets, or, if they’re lucky, bricks and mortar.

Just before rolling into Durban — notorious not just for hot summers, but stiflingly humid ones — I’d scanned the first report coming out of their project collaboration with the local civil society organisation Project Empower.

One graph is a stop-you-in-your-tracks bit of data: temperature spikes inside the homes are easily 15°C hotter than the local Ballito weather station. Where the station registered 35°C outside, the i-buttons logged nearly 50°C inside the Dakota Beach homes.

Fifty degrees Celsius.

That’s enough to stop the strongest of hearts.

Hokkies, not play houses

My home for the week had looked quaintly rustic on the website. Given the price, I expected it to at least be habitable. And surely a proper structure with actual roof should be? I flung the windows wide, drew the thin curtains on the blazing-hot-side of the hokkie, and fired up the fan. But the sun’s energy, hitting the tin roof, seemed to be greater than the sum of the parts. The laws of thermodynamics inside Wendy house took care of the rest.

At first, the mood was one of bemusement.

Not great, but it’ll cool down soon, surely?

Four hours later, my heart was thundering like the great wildebeest migration, my head pounded like a funeral drum (channeling Roger Waters here), and my mood was blistering like I’d scalded my skin over an angry kettle. [Sometimes one has to break the rule about not mixing metaphors, sorry language nerds.]

There was no escape: outside = sun; inside = furnace. Lost the will to form complete sentences. Pen down. Dazed.

By lights-out, the bed was the epicentre of an unsafe universe that seemed desolate and inescapable.

Monday arrived with cooler air, but with a few light sprinkles of tears. We spent the morning moving from home to home, sitting on people’s neatly-made beds as they chatted about their lives in Dakota Beach, and spoke of the discomfort of a heatwave as if it’s a normal part of life.

By the time we wrapped up, my mood had become more throaty and thunderous.

Is this our collective future, I wondered? The life of the average person in an informal settlement, the ones that most of us turn away from because we don’t want to be confronted by this reality: is this what awaits all of us? The question is not so much that we’ll all end up in informal settlements — although climate migration is going to uproot many more of us than we currently realise, and we don’t know where we’ll land — but the heat, the heat, the inescapable blistering, brain-melting heat.

Hot as Hades

Part of the i-button work was for participants to record daily voice notes, giving a personal account of how they’d experienced conditions on any given day. Many described themselves as feeling tired, or were apologetic for being lazy on hot days, not realising that what they were describing is something far more serious: heat isn’t just uncomfortable. It can make us properly sick. It can even be lethal.

This is what’s tee-ed up for the next chapter of Story Ark. But behind the calculated storylines and edited photo essays is a turbulent week that’s left me on my knees.

I checked out of the tourist shack after one night. Once Monday’s work was done Mouse and I drifted around Durban in our little plumber’s van looking for somewhere to stay but my brain felt moribund. I couldn’t seem to trouble-shoot my mood or the predicament of having nowhere to drop anchor that night.

By mid-afternoon, I turned the good ship Story Ark inland, and made my way back to the bricks-n-mortar home we’d been squatting at for much of August.

I’ve been lucky. Through all these heat episodes we’ve had an escape hatch. The people I’m about to write about don’t.

Nothing quite like walking in another person’s shoes to build some empathy, even if it’s just for a few short steps.

Stay chill, and chilled.

Leonie

Itinerant reporter, captain of the good ship Story Ark, and travel companion to the irrepressible cat called Mouse.

*Mouse was in the care of loving cat-sitters at the Project Empower offices while I did the field work on Monday, and was safe from the heat.

Into the flames

If Story Ark’s departure day had been written as a screen play, it could have been penned by Dante himself. There were no dock-side ticker-tape parades. Story Ark set sail eight months ago, on 6 October 2024, and it was a shocker of a day. There were no streamers, no bottles of bubbly exploding extravagantly over the hull as we hoisted anchor mid-morning on that Sunday, and sailed away from the safe harbour after nearly three decades of living the high-life in Cape Town, South Africa.

Story Ark’s departure day was like a screenplay from one of Dante’s lava-levels of hell.

We set sail eight months ago, on 6 October 2024, and it was a shocker of a day.

There were no dock-side ticker-tape parades. There were no streamers, no bottles of bubbly exploding extravagantly over the hull as we hoisted anchor mid-morning on that Sunday, and sailed away from the safe harbour after nearly three decades of living the safe life in Cape Town, South Africa.

There was a quavering farewell with friends, tears in a cavernous lounge of a former-home, the dead-bolting of a kitchen door that was no longer mine to open, and an uncertainty unlike anything I’ve known in the many years I’ve travelled far from home to find ‘the story’. I've done many trips over the years, some with companions, usually solo, but I’ve always had a home to come back to.

Now, home was wherever the van’s engine idled. At the time, this was liberating and terrifying in equal measure. It still is.

Cooked

The day started at 4am, two hours ahead of the alarm. The final packing of the van dragged on well beyond departure time, taking so much longer than anticipated. When we finally pulled out of Cape Town, we stuck to the best harbour protocols: slow as you can, this is a wake-free zone.

It was only when we hit the high seas of the N7 motorway that something on the dash began to flash a warning, and it wasn’t the engine over heating.

Something far more horrid was on the stew. Outside, the ambient temperature hit 29°C, then 31,5°C, then 34°C, 36°C, 37.5°C… by the time we rolled into the outskirts of Clanwilliam, four hours’ drive north of Cape Town, I thought the dial would break. It was 39°C outside.

39°C.

Earth’s average temperature has climbed by 1.5°C since the first fossil-fuelled industrial machines fired up three centuries ago. Doesn’t sound like much, right? But if this average temperature were a child, they’d be spiking the kind of fever that’d have us rushing to the nearest emergency room.

A 1.5°C average temperature begins to look like the kind of extreme heat event that hit the Western Cape with a fever on that October spring day.

In that brain-melting bewilderment, I drew on the wisdom of comrade-in-arms ma-gogo Margie. When I’d laid bare my anxieties ahead of departure, about going off on this insane venture, she said pithily:

‘Go. It’s not going to get any cooler.’

She wasn’t wrong.

Day one of Story Ark was supposed to be easy, a trial run for longer, harder, harsher exposure to the elements, to solitude, to living out of a tent from time to time, to the rigours of investigative research in the most off-grid conditions.

I didn’t anticipate what was to come on that maiden voyage, of how it’d feel to aim for the distant curvature of an unknown horizon, with my back turned to all the security I’d known.

In that first day, there was also a moment of getting lost in a phone dead-zone in the Cederberg mountains because I was muddled by tiredness, heat, and probably a bit of oh-my-f*ck-what-have-I-done. So I missed a few important off-ramps and right-turns, and boom, next thing I’m in the middle of a directional dead-zone with a distraught cat who was wailing like she was mourning the dead, and there was nothing that I could do to ease her suffering.

When we finally dropped anchor at our first stop, a camp site in the Biedouw Valley in the Cederberg, it should have been mid-afternoon. Alas, the sun was bloating on the horizon but no less foul-tempered. The van tiptoed down the sandstone-y road and onto the cropped lawns next to a river which, if nearby rock paintings are to be believed, show that foragers were bedding down here a good two or three thousand years ago. It was good to join the club.

At reception, I hoofed away some overly zealous house dogs, and made an executive decision. Bugger the tent idea. After such a hellish day, we were taking a chalet.

The cat called Mouse, the chief navigator and plucky comic relief, was unrecognisable on the first night. She wouldn’t leave my side, sticking to my heel and yelling with nerve-jangling ferocity whenever I took a step anywhere. In spite of her irrepressible spirit, even she needed reassurance that the world wasn’t coming undone. I couldn’t give her any assurances. I still can’t.

What the hell had I done?

What the hell have I done?

The voice messages dispatched from my phone the next morning were a morse code of snot-en-trane.

But there was no going back. I’d sold my home to pay off the debt following a few years of collapse in the journalism sector. I’d cobbled together a crazy scheme to salvage my career, even as the climate seemed to be unravelling.

If the Titanic’s going down, I told myself, I’m still going to put myself to good use, even if it’s just rearranging the deck chairs and telling everyone there’s no point in panicking.

The idea: untether from the cost and hassle of a home and office. Become an itinerant reporter, moving from place to place in search of the tales that will show how the climate crisis is unfolding on our doorstep, in our lifetime. Hammer out the stories from a tent, Hemingway style. File copy from wherever there’s cellphone signal.

It seemed so romantic, so easy, from the safe side of departure day, from the secure side before you sign away your home with an offer-to-purchase agreement.

True as (non-) fiction

Humans are meaning-making animals. We tell stories as a way to make sense of the world amidst all its uncertainty and suffering. Viktor Frankl nailed it down in his book Man’s Search For Meaning.

Yes, journalism has collapsed. I’m not the only reporter to have lost chunks of their livelihood recently, and that’s before AI elbows us away from the keyboard. Yes, the climate is unravelling far faster than scientific models foretold.

But how we survive these disquieting times, indeed how I survive as a newly-minted roving reporter, depends on the meaning we find in things. This isn’t about being a pollyanna. There’s room for reality. But where possible it helps to push back against the darkest reading of circumstances, if we can.

Am I a broke, homeless, middle-aged woman living out of a van?

No. Not for a second.

I’m a woman of such privilege that I can choose to be a childless cat lady, who has so much agency over her life, her body, her savings, that she can travel the country looking for climate stories, and do work that feels important, meaningful, and life-giving.

Because of this privilege, I have a duty to use this for the greater good. To tell the stories of those who can’t do it themselves.

That sounds self aggrandising. But if I didn’t convince myself that there was a greater good in the dis-ease of that first tumultuous day, I wouldn’t have had enough ballast in the hold to keep going. I wouldn’t be able to keep tending the sails as future storms rolled through. And there were plenty to come. You’ll read about them here, in the Captain’s Log.

Story Ark is an adventure, for sure. But even the best adventures come with sunburn, seasickness, and a hankering for stable ground under one’s feet from time to time.

This diary entry should have been written on Monday 7 October 2024 as I kicked back in a hammock, throwing myself delightedly into the embrace of a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

Alas, it seems I needed a few months to wrest the quill from Dante’s cold dead hands so I could find a way to tell a story where the author is allowed to be honest but doesn’t sound too forlorn.

There've been many glorious days since this first one. But the first one was enough to make even the most salted seafarers question the wisdom of this voyage.

Thank you for sailing with us into these uncertain waters.

The Captain’s Log will that document the journey as it unfolds over the months and years since departure day.

Until then, and in solidarity,

Leonie

Itinerant reporter, captain of the good ship Story Ark, and travel companion to the irrepressible cat called Mouse.

Six months in, slow as can be

I used to think that a writer’s retreat was for divas, or wannabes with more money than sense. Until I tried one.

Time. The privilege of time for slow, deep thinking. And silence. Our brains need these to advance an idea and craft a story, in the way that a parched throat needs water. Story Ark is like one long writer’s retreat.

I used to think that a writer’s retreat was for divas, or wannabes with more money than sense.

Until I tried one.

Time. The privilege of time for slow, deep thinking. And silence. Our brains need these to advance an idea and craft a story, in the way that a parched throat needs water. Story Ark is like one long writer’s retreat.

It’s also a return to slow journalism.

I recently heard this called ‘artisanal’ journalism. Much like the idea of the writer’s retreat, this phrasing sounds a bit like overly-precious craft beer or hand-rolled facial hair that’s b’n sculpted with the tallow of a moss-fed yak from somewhere in the melting tundra, or what-what.

Slow journalism is really just a return to real journalism — cue: Paul Salopek’s extraordinary Out of Eden mega-walk. [Unashamed name-drop: Salopek and I shared the same National Geographic magazine editor, Oliver Payne.]

Slow journalism is how we should be doing the craft — taking time to dig deep, think hard, and do a fuller sweep of sources and experts. It’s the antidote to churnalism, where profit-driven commodified ‘produce’ has replaced news’s real function. Journalism should be a load bearing wall of a healthy democracy, where the job is to inform the public discourse, stoke active citizenry, and hold the powerful to account in the interests of the common good.

Slow journalism should also allow us to step away from our desks and get our boots back on the ground, out there in the communities where democratic participation unfolds in real time.

Story Ark is a pursuit of this old-school approach to the craft, albeit in a somewhat quirky form.

Cue disembodied narrator’s voice: Story Ark is a year-long journalist project where our intrepid writer is living out of a van and travelling under the guidance of chief navigator, the cat called Mouse. The mission is to find the invisible stories that show how the climate crisis is unfolding on our doorstep, in our lifetime.

Chapter 1 Dust Bowl is a wrap

We’ve been on the road for six months. The time and freedom have allowed such deep immersive research that I’ve only covered two geographies — the Namaqualand desert, and the grasslands of the Eastern Cape Highlands, Lesotho and the Free State. I’ve only now wrapped up Chapter 1 Dust Bowl, which includes eight stories from those first epic months.

What started out as a vague plan for a year-long project is fast growing into a three-year mission. If I hope to visit a wide range of ecosystems and places, and sink into the cultures and local economies embedded in them, the mission will need much more time on the road.

I’m about to disappear into a hermitage of sorts so that I can write the first stories for Chapter 2 Golden Threads and Chapter 3 Oil Spill.

Pimp my ride

As of this week, the good ship Story Ark will no longer sail incognito. The van will soon have some funky decal announcing our mission to the world. The virtual Story Ark is also getting a bit of a spit-’n’-polish: full social media clean up, and a website overhaul. Watch this space!

(Mis)adventures on the high seas

The (mis)adventures from the first six months on the road include, but are not limited to: one necrotic spider bite, two dune-drownings for the van, three slow punctures, and four sutures in a hand after a tumble off a medieval-style spiked fence the day before Christmas Eve. It’s b’n wild.

One final lesson from the road: If the spare tyre for your plumber’s van is stowed underneath the car, have some strapping lads move it into the van itself. You don’t want to discover that you’re not strong enough to brute-force the nuts loose with an ill-fitting tyre iron while lying on your back, in a frock, on the side of a secluded Lesotho road as the left rear wheel sighs quietly and deflates like it has a touch of the vapours and needs smelling salts.

If you’d like to get occasional Captain’s Log updates, please sign up to the newsletter. Otherwise you can follow us on whichever of the socials grooves with you.

Thank you for joining us on this Odyssean voyage.

Fondly, from afar,

Leonie Joubert

Itinerant science writer-slash-journalist, and captain of the good ship Story Ark.

Fabulously flotsammed

No one sets out to get into trouble. It’s usually a cascade of small events that take you from ‘fine’ to ‘not at all fine’ before you’ve had a chance to think things through.

Which is how I find myself I’m standing here, pleading for help, and hopelessly ill-equipped for a desert outing.

The man, when he appears, looks as derelict as the building he emerges from: a farmstead that’s just holding firm against an ocean of advancing orange dune sand pressing in on every side from a rim of distant mountains.

This might explain why he seems completely unmoved by the person standing before him.

A stout, middle-aged woman, red-faced from stress or exertion or both. Barefoot. In a frock, the kind you’d wear to the beach, not on a desert expedition. Hair, like it’s had a few too many volts from an electrical socket. No car. No handbag.

Did I say barefoot?

I’m not even one week into a multi-year mobile journalism project, where I’m travelling around the country in search of stories that show how the climate crisis is unfolding on our doorstep, in our lifetime.

Not one week in, and I’m already in a pickle.

I point to a speck of white in the distance. I want to explain that my little plumber’s van is belly-down on the sand and I need help. A tow, a telephone, anything?

He’s still unmoved. But he does tell me something about how he washed up here: having lived in ‘Die Kaap’, somewhere near Cape Town, and how someone screwed him over in his retirement and now he’s stuck out here as a caretaker or something on a relative’s farm and…

I’d come to this part of the desert in north-west South Africa because I’d heard that parts of it are turning to dust bowl: gravelly, hard-packed desert is turning into mobile sand dune. There’s one particular dune that’s becoming something of a celebrity amongst desert ecologists.

I had the NASA satellite images, the eyewitness accounts, the expert analysis, piles of papers and books. Now I needed to see for myself. I needed to meet this dune in person.

I don’t realise, as I stand at this man’s back door, that the dune has already found me.

Barefoot, but far from a kitchen

No one sets out to get into trouble. It’s usually a cascade of small events that take you from ‘fine’ to ‘not at all fine’ before you’ve had a chance to think things through.

Which is how I find myself standing here, expecting help, and hopelessly ill-equipped for a desert outing.

I’d left the travellers accommodation of the previous night, and was taking an early morning drive along a farm’s back road, paying more attention to filming the landscape than to the landscape itself.

This was a short cut to a nearby town, I was told, and I needed to do a reccie. The view was terrific.

Travel days need comfortable frocks and flip flops, I worked that out at the get-go. So when I find myself on my hands and knees, scooping sand out from behind the front tyres of the van, which is now resting on its belly and clicking as the engine cools, I’m not thinking about sensible shoes. The plan is to slip the mats from the wheel wells behind the tyres, so I can reverse out over them and rocket to freedom, tail-pipe first.

What was that about not setting out to get into trouble?

As I inspect the shredded mats, which, it turns out, can’t withstand the punishment of the tyres trying to get purchase, I see a cloud of dust in the middle-distance. It’s moving with the kind of speed that says it is, in fact, a car of sorts. Which means a road. And rescue.

I leave the starting blocks with the intention of Hussein Bolt, if not his form. Waving, yelling, soaring over the sand like a gold medal depends on it.

By the time the dust settles, and with it any hope that the driver has seen me, I realise I’m about half way between the van and a cluster of buildings I’d seen earlier.

I set a new course, putting still more distance between myself of the van, hoping for signs of life. It’s a farmstead for sure, but the kind that looks like one of those abandoned mining towns on the Namibian coast, disappearing under a determined tide of sand. But the smell of wood smoke says that someone does, in fact, still live here.

I holler. I call. I shout. That’s when the man appears. Grey bearded, hide cured to parchment. An Afrikaans accent salting his gravelly English.

By the time it’s clear that he’s not going to be much help — no cell; no landline; no-one answering his two-way; mostly, no will to trouble shoot — I realise I’m going to have to fix this myself.

I plod back to the car — less Olympian sprinter now, more determined castaway — and gear up for the rescue mission: umbrella, running shoes, bullet-proof sunblock, bottle of water… and the make-up mirror from my toiletry bag.

I’m not too far from the farmhouse where I’d hired a rustic chalet the previous night. If I hoof it back in that direction, I reckon I can get there in about 90 minutes, give or take.

Walk-trot, walk-trot, walk-trot, walk-trot.

The sun’s getting higher — it’s about 9am now, maybe 10, I’m not paying attention — but the heat’s still manageable.

Walk-trot, walk-trot.

It’s a bit further than I remember.

Walk-trot, walk-walk-trot, walk-walk.

Don’t fret.

Walk-walk-trot.

The pixel of a house comes into view, not quite shimmering through a mirage, but definitely and dramatically there.

Walk-trot, walk-trot, flash-flash-flash with the mirror. Walk-trot, walk-trot, flash-flash-flash.

Please let the farmer see me. Please let him see me. Please see me.

Walk-trot, walk-trot, flash-flash-flash.

There’s movement. The farm truck rolls towards the gate. If it turns left, he hasn’t seen me and he’s heading to town. If he turns right, I’m saved.

Turn right, turn right, turn right, please turn right.

…..?

…..!!

He turns right!

I’d come here in search of a dune. I’d come here with the satellite images, the eyewitness accounts, the expert analysis, all the academic papers.

What I didn’t know I needed was the folklore about how this dune came to be.

Before I can find the dune, the dune finds me. And in getting rescued from it I meet the people who are custodians of the local lore. Once the farmer and his entourage have pulled the van clear, we end up around a brandy-soaked dinner with the locals. I get all the gossip, going back generations.

I also hear the fable of the farmer, who, in years gone by, had taken out his wrath on his animals. A donkey, in particular, got the worst of it. One day, after yet another beating, the donkey pulled away from his abuser and plodded off down the dirt track. Then, he paused and looked back at the farmer.

A supernatural voice was heard from that donkey.

‘Why do you beat me so? From this day on, this land will forever be cursed.’

It was then that the verdant grassy plain which had fed so many farmers’ herds for generations — called, aptly in Afrikaans, ‘die grasvlakte’ — began changing to travelling sand.

Today the dune is swallowing up the homestead where this man now lives. A man who can’t rescue himself from his own fate, let alone me.